Project Arts Centre presents in partnership with RTÉ Culture

On the first weekend of each month, Project Arts Centre will publish a new work in partnership with RTÉ Culture.

Project Arts Centre has invited a number of artists, curators, and social activists, with a lived experience of intersectional discrimination, to discuss their practice and share ambitious and provocative new work, encouraging crucial dialogue around the impact of social and economic inequality.

In this fifth installment, commissioned artist Louis Haugh, and Fatima Groups United community development worker, Richie Keane, talk to Project Potential Coordinator, Cathy Coughlan, about their project Future Food, as part of the Rhizome Green Arts project.

Rhizome is a project initiated by Project Arts Centre in 2021, led by Artivist in Residence Maeve Stone and Artist in the Community Louis Haugh, in partnership with Fatima Groups United, NCAD Field & Trinity College Dublin. At its core, it seeks to connect local communities from different backgrounds and disciplines, in creative conversation about the future of our planet.

Watch: Rhizome – Green Arts Project

CATHY COUGHLAN: Hi Louis and Richie. Thanks for being here today. Maybe you would introduce yourselves and tell us a bit about your role within the project Future Food.

LOUIS HAUGH: Sure. My name is Louis Haugh. I’m a visual artist, born and raised in Dublin. I developed the project Future Food in collaboration with community members from Fatima Groups United and led the group through a series of workshops that explored the history of bread making and the future of food supply chains. Although my background comes from quite a traditional canon of photography and video, I’ve recently been more interested in developing a socially engaged practice. I’ve never worked well on my own and seem to be my most productive when I am engaging and collaborating with a broad community of people. I think artists hold a really valuable place within these communities and within society in general. We’re allowed to exist in this nuanced space when everything around us is presented in very black and white terms.

Before Future Food, I led a number of other socially engaged projects that focused on ecology and micro-histories. (If Trees Could Talk, 2021 and ONE HOUR ARCHIVE, 2019). These kinds of projects have really broadened the framework of my practice, and have allowed me to extend beyond the photographic image, which is such a joy for me, as I have so many interests that never really fit into what I thought my practice was or could be. Working in this way has given me a whole new set of tools and materials, so to speak.

RICHIE KEANE: My name is Richie Keane. I’m a community development worker here in Dublin, working with Fatima Groups United Family Resource Centre. FGU was established in 1995 around the regeneration of the old Fatima Mansions flats complex. We’re really about the economic, social, cultural, and environmental regeneration of the whole area. We operate from a purpose-built community centre called the F2 Centre and around 250 people come through our doors every week. Our participants come to our community work programmes, health and well-being programmes, fitness, ecology, arts, and culture programmes. We’ve also developed green and creative Prescriptions as part of our work for Dublin 8 Social Prescribing Service, so that’s the second route in. We’ve an open-door policy here really.

Before we got involved in the Rhizome project with Project Arts Centre, we had already been involved in a number of other Green initiatives. We hosted the Dublin Community Environmental Network for about two years before lockdown, so we had a bit of a green agenda going on, which meant there was a heightened awareness of environmentalism and ecology. We worked with Seoidín O’ Sullivan and Common Ground and were part of the Mapping Green Dublin project. We also met the late Richard Taplin, who was really just a ball of energy, and he set up the community garden that was recently dedicated in his name – Taplin’s Field Community Garden, off Thomas Street. We were also strongly linked in with Flanagan’s Fields, the Community Garden here on Reuben Street, where our own centre is. We were in that community garden, growing veg and planting stuff and hosting summer solstice storytelling in their geodesic dome. And then Louis came along, through the Rhizome project.

CC: Louis, can you talk a bit about your initial ideas for the project, and why you wanted to focus on food, as a starting point for the conversation around climate?

LH: Food is something that I’ve always been interested in, along with my two siblings, Emma and Ben. We were raised as a vegetarian family in the 70’s and 80’s. In a working-class Dublin council estate in Blanchardstown, you know, being ‘the vegetarian kids’ was weird. It was weird for us. It was weird for everybody else. Not everybody got us. People used to stop my Mam in the street and beg her to feed us a bit of chicken because they thought we were malnourished. They thought we needed the protein. Grannies at birthday parties would try and feed me cocktail sausages out of pity. And, you know, they were just totally perplexed when I said no.

Fast forward to me working part-time jobs while I was in college and as a graduate. I worked a lot in cafes, and in hospitality in general, like a lot of people in my situation did. I did a lot of baking, cooking, and serving of food. But, you know, it was always separate. It was always my part-time job while I got on with the ‘real’ work.

But over the last few years and in particular, during lockdown, those borders or separations have started to dissipate, have started to blur. One thing has fed into the other. And I think lockdown was the start of that, where I became really focused on making bread, as many others did during that time. And that became a routine. It became a way for me to keep track of the hours in the day, and the days of the week. And I didn’t know it at the time, but it was a really important ritual for me, to be consistently doing that. I felt a little bit like I didn’t have a ‘lockdown project’. Every artist I knew had their ‘lockdown project’, a play they had written, a new photo series, or some fantastic soundscape. And I just had all this bread that I’d eaten!

This project was the first big project I’ve worked on since lockdown and I’ve started to make serious connections. I’ve started to realise just how important food is to my creative practice. It’s like air and water. It’s the most important thing in the world. You know, we need food more than we need a roof over our heads. It’s a primal need.

I didn’t want to focus on the negative. I think there’s a lot of negative things you can talk about and discuss when it comes to climate change, like statistics, rising sea levels, fauna/flora extinction, soil erosion, water table depletion, etc… All of those narratives are terrifying and they almost paralyze you. It makes you feel as though you don’t have the skills or the ability to take action or do anything positive. I just thought that food would be a much more interesting and accessible way to approach the project.

The idea of sharing a meal with somebody is very special. You share meals on the most special of occasions. You share meals with your closest family at Christmas, you bring somebody to dinner for their birthday. You know, even at your funeral, there is a meal shared, in your name. All of these seminal moments in life are centered around a meal. So I thought that would be a really special way to direct this project toward positive, actionable change.

CC: Richie, how did the community react to the work and to that approach?

RK: Well, there’s been a tradition of food and nutrition here. We have an industrial kitchen. We’ve run programmes around healthy eating. So yeah, food was there. And every family cooks food. We have to eat. We started Future Food with Louis and it quickly became apparent that we had this lovely intercultural component in the room. We had participants from Algeria and from Palestine. So we saw different versions of hospitality, different recipes, memories, and micro-histories. The sociology behind all of that is fascinating.

It’s not that long ago that you would never go empty-handed to a house. You’d always bring brown bread or an apple tart, or you’d be given spuds and rhubarb or eggs that were freshly laid or cabbage that was grown, just picked up out of the field. A lot of people had ‘patches’ in the suburbs of Dublin in the thirties and forties because it was a time for resourcefulness. There was a lot of poverty. So you made everything stretch. You were self-sufficient. You were already organic, you know. We think it’s a new concept, but this is just in my memory, of my mother, and my grandfather, who was a gardener. It was just a gorgeous project. And I think Louis is exceptionally skilled at facilitating and being just a decent guy.

CC: Lovely, thanks Richie. Louis, can you talk a bit about the artistic outcome and the Future Feast you produced at the end of the project?

LH: In my mind, we produced a meal as an artwork. I think art is about making connections. Whether they’re connections within your own mind and creative process, or social and interpersonal connections. And I think what we did, over a series of about 12 weeks, was make those connections. We gathered together. We kneaded the same ball of dough. We worked in the same kitchen. We shared the same recipes. And over the course of the project, we nurtured those important connections.

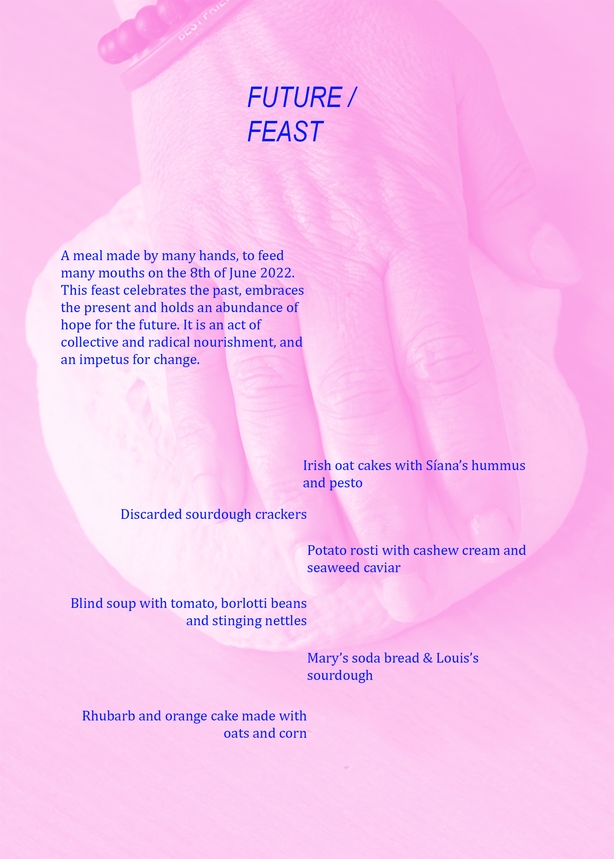

And as Richie said, it was an intercultural group, but it was also an intergenerational group. And there was a lot of shared knowledge and shared learning, which culminated in this feast on the 8th of June. And really, it was an artwork centered around our shared understanding of hospitality. We spent two days cooking in the kitchen in the F2 Centre in Fatima and each component of the meal was in some way a response to climate change or Ireland’s position within this idea of Food Sovereignty.

We had oatcakes made from Irish Oats (the first record of bread in Ireland). We had potato rosti, obviously made from Irish potatoes, served with cashew nut cream and this lovely seaweed caviar. So again, we’re thinking of the history of Ireland and Irish food, almost an acknowledgment of the famine, thinking of food that comes from the land and the sea. Then we had blind soup, which was Marie Maher’s memory of when she was a child. It was called blind soup because there was so little meat in it that you’d have to be blind to believe there was any in it at all. It was made with Irish tomatoes, borlotti beans, as this nod to the future of Irish agriculture and alternative protein sources, and stinging nettles from the NCAD Field. And then we finished that evening off with a rhubarb cake made with rhubarb from my own allotment, with Irish oats and cornmeal. Everything was 100% plant-based. This was important to me, I’m not a vegan but I think we all need to make as big a push as possible to change our daily habits, and this meal was a demonstration of that.

CC: It really was an incredible spread. I’m just wondering about the legacy of this project, and whether you will come back together in the future?

RK: There was a feeling that we would all come back together for harvest time and that we would make a harvest festival feast in October or November. Because in addition to Louis and ourselves working here at the F2 Centre, we were also linked with students from the NCAD Field. Artist and lecturer Gareth Kennedy and seven students were actually amazing, and we sowed rye, barley, oats, wheat, and potatoes in the NCAD Field. It was just lovely. And we’ve started this just gorgeous journey together, you know, of hope and resilience, because we don’t know what the climate crisis is going to throw at us.

LH: Yeah, I mean, we sowed the grain in the field in NCAD, almost as a way of making a commitment to harvest it in Autumn, because we knew the project would be concluded in June. The grain is also an acknowledgment of Ukraine – the world’s biggest grain provider, it’s either them or Russia, they’re #1 and #2. We got the awful news, I think the same week that the project kicked off, that Russia had invaded Ukraine. I don’t want to trivialize what happened, or what’s still happening, by only focussing on how this affects us in Ireland, but the future of our food supply was just so precarious at that stage. You know, something as fundamentally basic and important as grain, as bread. It just brought home the stark realization that our bread is reliant on global politics. For me, that was and is quite scary.

So we sowed the grain in the field as a community, and I think that speaks about the legacy of the project living beyond June. So yeah, I think there’s great potential and impetus there to keep going.

RK: I mean, it was amazing. There is so much inherent wisdom that is stored in our folk memory and in the experiences that we had growing up. You know, all the big questions that we were thinking about as we spoke over a hot griddle or were waiting for bread to bake in the oven. It was just a really nice time for us.

Accessibility

If you have any questions or feedback about accessibility, please do not hesitate to contact us at access@projectartscentre.ie or call 01 8819 613. You can find the latest information about Project’s accessibility here.

Funding

These commissions have been produced in partnership with RTÉ Culture.

Project Arts Centre is proudly supported by The Arts Council and Dublin City Council.