Project Arts Centre presents

Jeremiah Day & Simone Forti

Jeremiah Day is interested in resistance movements, as well as the flux of knowledge, stories and identity through the migration of people and histories. Day has been researching the movement of the people of the Blasket Islands off the Dingle Peninsula (Ireland), to the town of Springfield near Boston (USA) culminating in a complete evacuation of the Islands in the 1950s.What we know of the poetic tradition of the Blasket Islands comes to us largely through the efforts of the English linguist George Thompson. In the story-telling of the Blaskets, Thompson felt he’d found a link with the pre-Socratic tradition of Greek epic poetry, where spiritual, personal, political and practical subjects were integrated, and thus the boundary between art and life could be said not to exist at all. Springfield has been largely in decline for fifty years now, a classic post-industrial American city. Can we imagine that any of the story-telling traditions of the Blaskets have lived on, there? And though the Blaskets are long deserted, what of the now developed Ireland around them? What does progress mean, from the lens of the Blasket tradition?”Poetry proper is never merely a higher mode of everyday language. It is rather the reverse: everyday language is a forgotten and therefore used-up poem, from which there hardly resounds a call any longer.” – Martin Heidegger Jeremiah Day

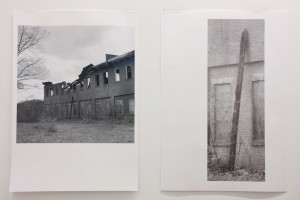

News Animations / No Words For You, Springfield consists of a new series of photo-works by Day, meditating on the city of Springfield as the end point of the Blasket story-telling tradition. He also invited legendary dancer Simone Forti to present for the first time in the visual arts context her practice of “News Animations” – a body of work Forti has developed since the early 1980s, improvising movement and speech from the content of the daily news. A member of the pioneering Judson Church Group, Forti’s work has been shown at the Whitney Museum of Modern Art in New York and recently at the Serpentine Gallery in London.Whilst in Dublin, Forti and Day worked together to create a new collaborative improvisation performance. If Jeremiah Day’s practice oscillates between the creation of text and image, Simone Forti bisects his axis with her interest in text and movement. The resulting collaboration – Open Form was premiered in Project’s Gallery at 6pm on 25 March, and the documentation plays throughout the exhibition in Project’s Foyer space.

ON SPRINGFIELD

Douglas Valentine is an author currently writing from Longmeadow, a suburb of Springfield Massachusetts. He is a regular contributor to Counterpunch magazine and the author of several books on political history, including the definitive study on the C.I.A.’s Phoenix Program in Vietnam, and The Strength of the Wolf: The Secret History of the War Against Drugs, with it’s sequel The Strength of The Pack forthcoming in 2008. In the late stages of preparing this exhibition, Jeremiah Day discovered that Valentine was writing from Springfield and approached him to engage in a dialogue about Day’s project.

Questions on Springfield for Douglas Valentine:

I used to teach elementary school in Los Angeles, and one day I realized how many of my students were from Central America – El Salvador and Guatemala in particular. A large portion of these children’s parents had fled to the United States to avoid the chaos and violence of those countries civil wars, but ironically had fled to the country largely responsible for those wars, as the United States had basically initiated and managed them. It was one of those rare moments when I could feel how I lived in a landscape that was alive with the consequences of what are usually abstract political ideas, and where the underlying causes of my daily condition were clear.

In light of your work on broader historical and political questions, do you ever see your local situation in this way? How does Springfield seem to you, when viewed through the prism of the repressed chapters of American history you have pursued?

Most of the people I meet around here are from here, while I was born in Pleasantville, New York, and lived in a lot of other places before I got here 15 years ago. It’s not my hometown and I do not have a lot in common with the hometowners. They have extended families here and friends from school. Their brothers are cops. The cops are basically the first line of defence against the Puerto Ricans and Blacks. The Italians (80 families came from one village in Italy) in the Little Italy part of Springfield resent the encroachment into their decaying neighbourhood. There was a Mafia murder here about four years ago right across from the Italian deli I go to every Saturday. The local TV station interviewed me about the murder because they knew about my book Strength of the Wolf. I said that Al Bruno, the Mafia boss that got killed, was probably an FBI informant. The next day, some people at the gym I go to wouldn’t talk to me. Comments were made. Al Bruno’s son goes to my club. The daughters of Mafia bosses marry cops in town. About ten years ago a guy at the club was, by coincidence, the son of a narcotics police captain in Springfield. We became pals and would shoot pool and drink beer at bars together. One day he told me a secret his father had told him, that the cops in Springfield allowed the Mafia bosses to bring drugs into town and, in exchange, the Mafia bosses told the cops the names of the Puerto Rican and Black distributors they sold the dope to. That way the cops could keep making busts and keep the pressure on the minority community. Eight ball in the side pocket.

There’s a big law firm in town: Ferriter & Scobbo. The Irish I know in town know nothing about Blasket Island. I have Irish citizenship because my wife’s father came from Ireland. My own Scottish ancestors came from Donegal, near Blasket Island. Strange.

Springfield seems to me like normal hometown America. The people here like it. It’s their home. There’s a big air force base, Westover, on the north side of town. Smith and Wesson has a factory here. The people understand why we’re in Iraq and Afghanistan and they support the troops. They support Israel and think Palestinians and Arabs are sub-human. If we talk politics, it gets heated.

Living here in Longmeadow, next to Springfield, I feel like a Martian. I write about the CIA and the DEA. When my work comes up, mouths drop open. There are a few radicals who would like to know what’s in my head, but even they eventually realize my experience is a wild story of cast away sailors in distant strange lands they have no way of confirming or denying. I exist here in a state of suspended anticipation of the next epiphany.

What we know of the poetic tradition of the Blasket Islands comes to us largely through the efforts of the English linguist George Thompson. In the story telling of the Blaskets, Thompson felt he’d found a link with the pre-Socratic tradition of Greek epic poetry, where spiritual, personal, political and practical subjects were integrated, and thus the boundary between art and life could be said not to exist at all. The Blaskets had poetry in the sense understood by Martin Heidegger – “Poetry proper is never merely a higher mode of everyday language. It is rather the reverse: everyday language is a forgotten and therefore used-up poem, from which there hardly resounds a call any longer.” And this everyday speech, infused with song and meaning – the anti-thesis of the “dis-enchantment” of the modern world – explains the appeal and resonance of the books which are artifacts of this tradition.

By the time it was decided to evacuate the Blasketers in the 1950’s, one islander said there were more Blasketers in Springfield than on the island. The cause for immigrating to Springfield among other places has been theorized by one transplant as “like when one bird settles on wire, and then another and then the whole flock comes over to join.” – Even in this description is contained the echo of the poetic imaginary of the Blaskets, and in my mind their “enchantment” seems to pervade my thoughts of Springfield. But I wonder do you find any such magic there? Can you feel any embers of that poetic tradition that was transplanted and then lost?

There may still be embers of that tradition in Springfield. The Portuguese immigrants have it in Ludlow. At their annual fair, a group of about 50–60 men break away and go across a field under a big oak tree and, in the middle of the circular mob, two or three or four men sing to–at each other; the singers change places but the song is constant, a kind of rap music in which the guys poke fun at each other in verse, truly amazing, impromptu jazz. I’m not involved with any Irish groups in Springfield so I don’t know about them. Personally, I find the magic everywhere because I am that tradition. People here are attracted to me, despite my being an outsider, because I speak poetically and have strange stories to tell about a world outside theirs. I spoke recently at a Unitarian church about my books. The people were enthralled. People ask me questions all the time; they come to me like they go to a movie theatre. Other times I project total disdain for this parochial place and people find me odd and off-putting. I don’t care. As part of the poetic tradition, it doesn’t matter to me where I am – be it Springfield, Saigon, Paris or Caracas. The dolmens, cairns and runes of my forefathers are embedded in my brain cells. I would be outside anywhere but in the forest. A piper in a Highland glen.

Springfield and the Blaskets have some things in common – it could be said both have been left behind by progress. The demise of the Blasket tradition was due to the islanders desire for access to “modern life.” Perhaps entering the modern world of factory jobs and political bosses need not have ended their poetic tradition, but in this case it seems it did. And the Islands themselves are now only home to ruins of a lost way of living.

Similarly Springfield is often said to have been “left behind.” Once a major center during the height of the industrial revolution, Springfield seems to have led American cities into post-industrial decline, even sooner then “rust-belt” cities like Pittsburgh and Detroit. Springfield has been increasingly poor and shunned by its neighbours since the Second World War, when many of the larger skilled manufacturers moved away. From your vantage point in Springfield, how do you see the progress of the rest of the United States? Particularly in rock music there is a sense of the old industrial cities as a kind of golden age of high wages and full employment, which are compared to the ‘precariousness’ of contemporary service jobs. Does some of your vantage as writer and essentially a critic of contemporary American life stem from your local context?

“Pity that poor monster manunkind, progress is a comfortable disease.”

There used to be great rock bands here, playing the clubs downtown, then the club owners realized it was cheaper to spin disks and the bands vanished. That was ten years ago. The musicians got service jobs or moved to Northampton or Boston.

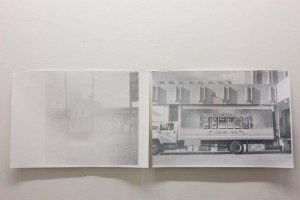

America to me is a tractor trailer truck, a convoy of tractor trailer trucks, hurtling along the interstates, in the rain and snow, the heat of summer, at night, always delivering the consumer goods and you’d better get out of the way. Springfield is another stop along the materialistic road to heaven. Remember, the Simpson’s live in Springfield. It’s the same here without the conscious parody. To me, it’s pantomime.

Springfield, as a metaphor of America, keeps me honest and hopeful, depressed and out of control. I’m an orphan of America like the old beat poets. There are lots of pretty girls, and I can make some of them fall in love with me, if I want to use my poetry that way. But remember what happened to the pied piper…..

Do you see your own role as a kind of storyteller? Your work could be said to seek to reveal hidden truths, to explain the causes for our condition. Given that there is no longer such an oral tradition available to you (I imagine), do you see that your work might still have a “call”, in Heidegger’s words?

Yes that’s how I see myself, and maybe yes to the second part, as there is an oral tradition in America, but I don’t know Heidegger’s meaning of call. I hear the call every minute. And for someone like me, the call doesn’t come from an audience. It’s just something I have to do, like a cat chases birds. Like the old blues song goes: “How long can a bird sing? As long as he knows his song. And that’s just how long a fool can go wrong.”

Events

PERFORMANCE

6pm, 25 March – An evening of performance – featuring a slide-show work by Day, improvisation and poetry from Forti, and a new collaborative improvisation developed for Project Arts Centre.

GALLERY DIALOGUE

5PM, 27 March with Jeremiah Day and Simone Forti

Disclaimer

Closed Sundays & Bank Holidays